CNN-guided Mask-RCNN for Organ Localization

Healthy and Pathological Kidney Localization in CT

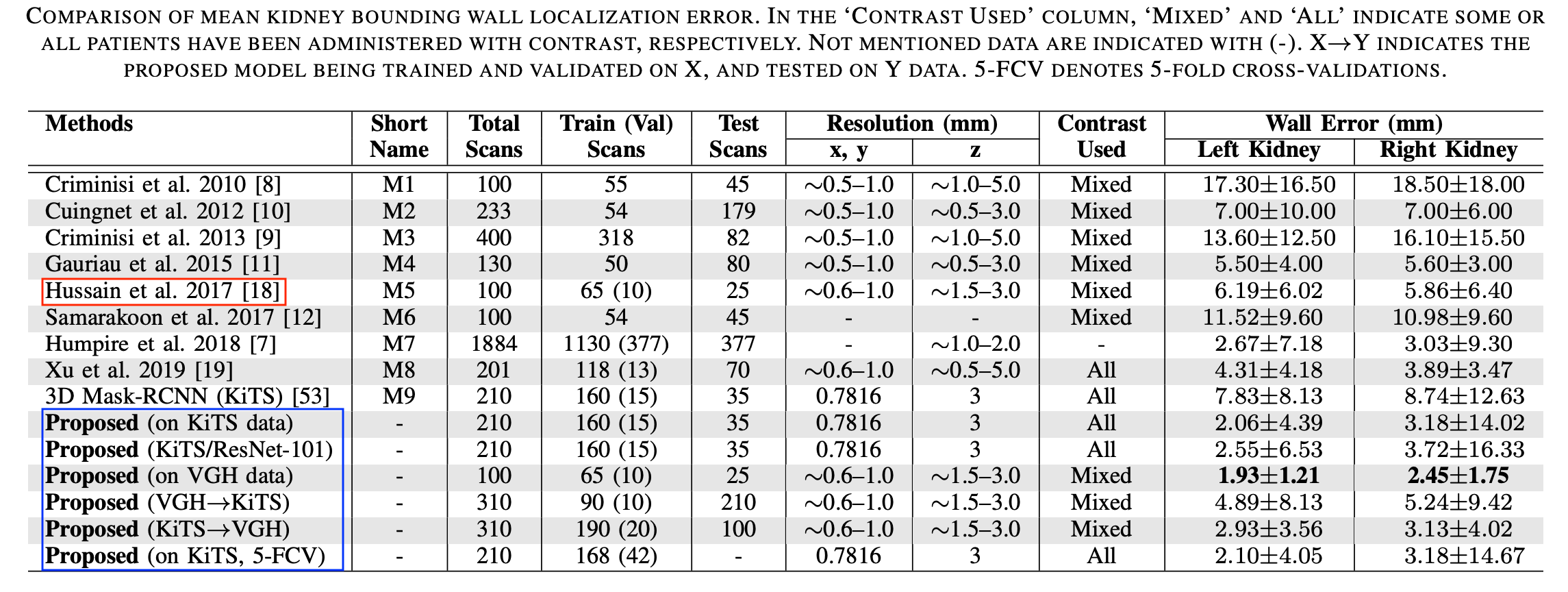

Automatic kidney localization in volumetric medical images is a critical step that often precedes subsequent data processing and analysis. For years, kidneys were typically localized manually in clinical settings. To automate this process, Criminisi et al. (2011, 2013) proposed regression-forest (RF)-based anatomy localization methods that predict the boundary wall locations of a tight region-of-interest (ROI) encompassing a particular organ. However, their reported boundary localization error for typical healthy kidneys (size ∼13×7.5×2.5 cm3) was 16 mm, which could significantly affect the subsequent volume estimation, depending on the volume estimation process. Cuingnet et al. 2012 fine tuned the method in (Criminisi et al. 2011) by using an additional RF, which improved the kidney localization accuracy by 60%. However, the authors mentioned (in Cuingnet et al. 2012) that their method was designed and validated with only non-pathological kidneys. Recently, Lu et al. 2016 proposed a right-kidney localization method using a cross-sectional fusion of convolutional neural networks (CNN) and fully convolutional networks (FCN) and reported a kidney centroid localization error of 8 mm. However, the robustness of this right-kidney-based deep learning model in localizing both kidneys is yet to be tested as the surrounding anatomy, and often locations, shapes and sizes of left and right kidneys are completely different and non-symmetric. In our priliminary work, we proposed an effective deep CNN-based approach for tight kidney ROI localization, where orthogonal 2D slice-based probabilities of containing kidney cross-sections are aggregated into a voxel-based decision that ultimately predicts whether an interrogated voxel sits inside or outside of a kidney ROI. In this subsequent work, we extended our previous work by using an effective CNN-guided Mask-RCNN approach for efficient kidney localization in CT.

CNN-guided Mask-RCNN for Kidney Localization

This improved kidney localization approach is a three-step pipeline (Fig. 1, boxes at bottom row). In the first stage, we use a kidney span detection CNN (S-CNN) classifying 2D axial slices, enabling a rough detection of the targeted kidney span along the axial direction. In the second stage, we use a Mask-RCNN to detect the 2D kidney bounding box along the coronal and sagittal directions. In the third and final stage, we use the same MaskRCNN to detect the 2D kidney bounding box along the axial and sagittal directions. Since RCNN typically produces falsepositive kidney bounding boxes in those slices that do not contain the kidney, the CNN pipeline of our method controls the choice of slices (fed to the RCNNs) by extracting those from kidney-containing regions by using S-CNN. We sequentially provide technical details and justification for different design choices in the following sections.

Data

We used 100 patients’ CT scans accessed from the Vancouver General Hospital (VGH) records with required ethics approvals by the UBC Clinical Research Ethics Board (CREB), certificate number: H15-00237. There were a total of 200 kidney samples, and we used 130 samples (from 65 randomly chosen patients) for training, 20 samples (from 10 randomly chosen patients) for validation, and the remaining 50 samples for testing. Our dataset included 12 pathological kidney samples (with endo- and exophytic tumors), and our training and test data contained six pathological cases each. We made sure that kidneys from the same patient were not split across the training, validation, and test cases. These data were acquired using a Siemens SOMATOM Definition Flash (Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Erlangen, Germany) CT scanner. Ground truth kidney bounding boxes were calculated from manual kidney delineation performed by an expert radiologist.

We also used 210 patients’ CT scans from the 2019 Kidney Tumor Segmentation (KiTS) Challenge database. This database contains patients’ scans accessed from the University of Minnesota Medical Center records. These patients underwent partial or radical nephrectomy for one or more kidney tumors between 2010 and 2018. We used 160 randomly chosen patients’ data for training, 15 randomly chosen patients’ data for validation, and the remaining 35 patients data (70 kidney samples) for testing. Here also, we made sure that kidneys from the same patient were not split into the training, validation, and test cases. We also collected the kidney segmentation data from the same database.

Results

For Details

Please read our papers [1].