Bone Detection in Ultrasound

Detection of bone surface in ultrasound using combined elastography and envelope signal power

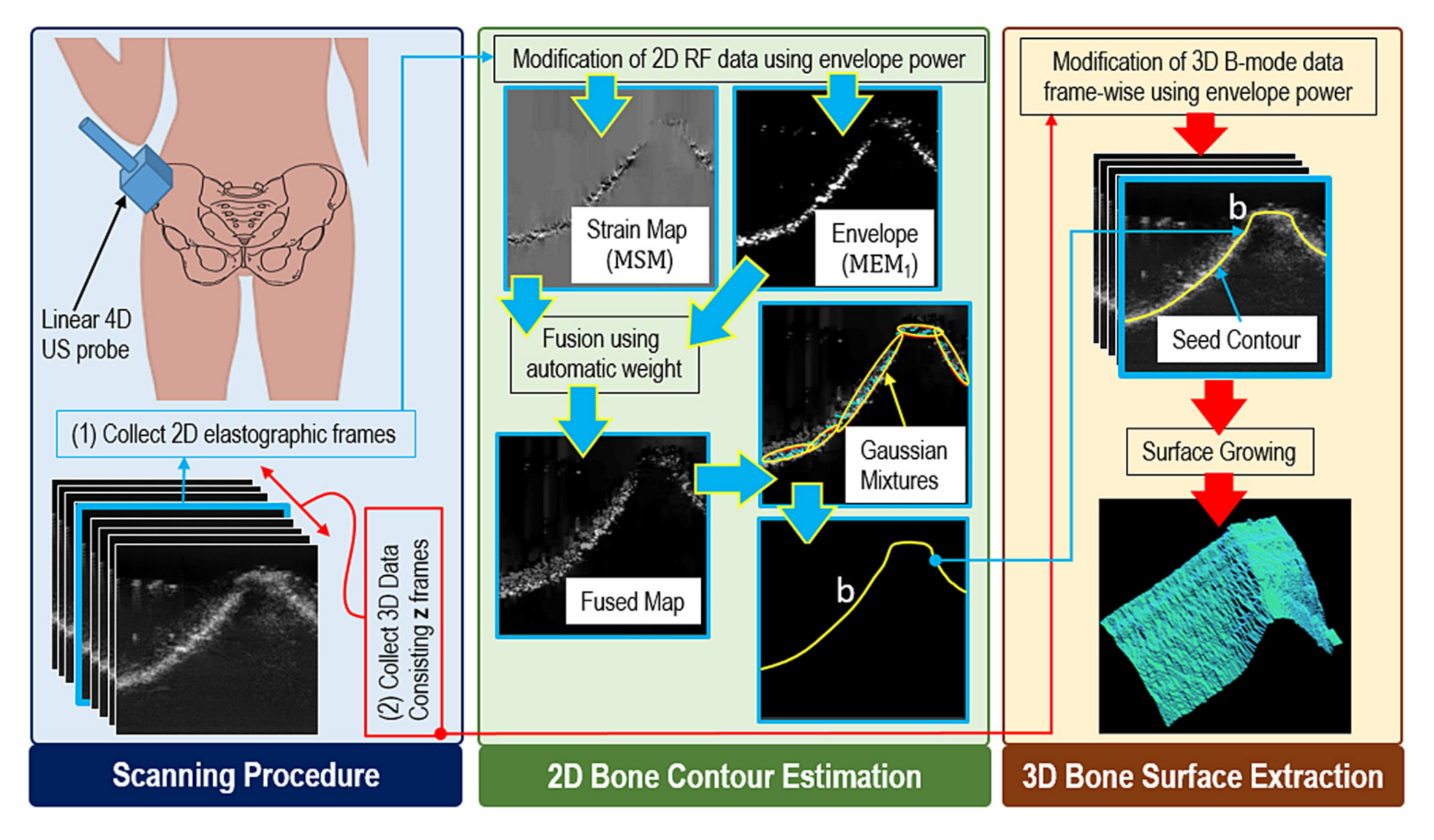

Fluoroscopy remains the primary intraoperative imaging modality for bone boundary visualization in computer assisted orthopaedic surgery systems. The associated radiation exposure posing risks to both patients and surgical teams gave rise to recent interest in safer non-ionizing real-time intraoperative imaging alternatives such as US. In US guided surgical intervention, bone localization in US images is essential for visualization and guidance, e.g., during fragment positioning in fracture reduction surgeries. Despite recent advancement in US intensity-based automatic bone segmentation, results remain unpredictable due to the high levels of speckle noise, reverberation, and signal drop out. To tackle this challenge, we proposed an effective way to extract 3-D bone surfaces using a surface growing approach that is seeded from 2-D bone contours. The initial 2-D bone contours are estimated from a combination of ultrasound strain images and envelope power images.

Bone Surface Localization

This work has two steps: (1) At first, we estimate the 2D bone contour from a pair of RF frames taken with and without a little compression. To estimate the bone surface location in this pair of 2D images, we used a real-time strain imaging technique developed by Rivaz et al. (2011), which is based on an analytic minimization of a regularized cost function. The resulting strain image was fused with the envelope power map using a weight. The weight was selected based on an empirical analysis of the mean absolute error (MAE) between the actual and estimated bone surfaces for different weight values. The weight for which the MAE was lowest in this pilot data set was used throughout our experiments. Then we used local linear fits over the maximum intensity point along each scan line of the fused map to produce the final bone boundary. (2) Finally, having identified a seed contour in the 2D elastographic image, we next use a surface growing approach to extend this contour laterally through the 3D volume set.

Data

We acquired eight sets ofin vivo US data, five of which were acquired for 2D evaluations from five volunteers (volunteer I: 25-y-old man, volunteer II: 33-y-old man, volunteer III: 26-y-old man, volunteer IV: 24-y-old man, volunteer V: 27-y-old man), and three sets of data were acquired for 3-D evaluations from three volunteers (volunteer VI: 27-y-old man, volunteer VII: 26-y-old man, volunteer VIII: 29-y-old man) after obtaining informed consent. All data were acquired with freehand compression. The US images were acquired using a SonixRP (Ultrasonix Medical) scanner in the Center for Hip Health and Mobility, Vancouver Coastal Health Authority. Here also, we used a L14-5/60 linear array probe operating at 10 MHz and a 4DL14-5/38 linear 4D array probe operating at 5 MHz to collect data for the 2D and 3D implementations, respectively. The study was approved by the UBC clinical research ethics board

Results

For Details